Mohammad R. Salama, Islam, Orientalism, and Intellectual History: Modernity and the Politics of Exclusion since Ibn Khaldun. London and New York: I. B Tauris, 2011.

Jadaliyya: What made you write this book?

Mohammad Salama: There were a few reasons that compelled me to write this book. First, I am a Muslim who has been living in the US since the September 11 attacks, and I have witnessed the dire consequences of those events on personal and public levels. After so much misinformation about Muslims and Islam invaded the public sphere and was unfortunately widely believed, I felt that it was urgent to address the roots and history of Islamophobia so that the reader would have a grasp on how Islam has been seen and understood in Western Europe and in North America (which are not identical when it comes to the treatment and perception of Muslims). My hope is to open a forum for a deeper understanding of Islam in the Western world. Instead of looking at these issues in isolation, I see them as part of a larger history of interaction between the so-called East and West.

Secondly, I aim to contribute to scholarly understandings of this complex relationship by looking at both Islam`s image in the West and its connection to the rise of modernity and the consequent onslaught of colonialism that Europe visited upon the Arab world, using Egypt as a case study. I wanted to lay bare the constructedness of some central narratives that Europe has used to write its own history as well as the history of Islam — narratives that are still present today.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does it address?

MS: This book brings together areas of inquiry in the Middle East and Europe that have not previously been studied as a single unit, connected together through a crooked line of intellectual history. I aim to demystify assumptions about Islam that pervade current discourse in the US and Europe. I investigate several watershed moments in depth, from Hegel`s view of Islam to nineteenth-century British epistolary texts to classical and modern critiques of ibn Khaldun`s thought. Through this in-depth analysis, I seek to point out that the core of the problem is not a clash of civilizations, as some polemicists argue, but a chronic case of cultural amnesia, one in which Euro-America refuses to acknowledge its share of responsibility in this complex and vexed history.

[This mural in the Main Reading Room of the Jefferson Building at the Library of Congress places Islam in a position that

indicates the inclusiveness with which America faced Islam more than a century ago. Image from unknown archive.]

The book also examines the underlying assumptions of the grand overarching narratives that European historians have constructed in the writing of world history and the role that these “meta-narratives” assign Europe in the development of human civilization, especially with regard to Europe’s relationship to Islam and the Arabic-speaking world.

J: How does this work connect to and/or depart from your previous research and writing?

MS: Much of my previous work has focused on modern and postcolonial Arabic literature, particularly Egyptian literature. This book uses literary texts in the service of historical understanding, but it also relies on these literary narratives to reflect on deeper layers of thought at work in history, in order to examine the complexity of the two disciplines. This book also addresses a more general post-post-colonial context, which has thematic connections with German Colonialism: Race, the Holocaust, and Postwar Germany (Columbia University Press, 2011), which I recently co-edited.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

MS: I hope to reach a wide audience comprised of readers from academe and the general public, people who are interested in the East-West relationship and its historical trajectory.

It should be of particular interest to students and scholars interested in Islam, European colonialism, postcolonial studies, and intellectual history, as well as an academic readership made up of people who want an overview of current trends in scholarship on Islam. These include scholars and students in interdisciplinary global studies as well as those interested in Middle Eastern history, the history of colonialism, and issues of human rights in light of the colonial past and current treatment of Muslim immigrants in the West. I hope it is useful to anyone seeking to supplement their understanding of any of these topics.

[Mohammad R. Salama. Image provided by the author.]

J: What other projects are you working on right now?

MS: I am working on a book about the politics of revolutionary thought in modern Egyptian literature. It deals with how political revolt, rebellion, revolution, and mutiny have been portrayed in Egyptian literature as well as how literature has influenced and helped bring about revolutions, both on and off the page.

Excerpt from Islam, Orientalism and Intellectual History: Modernity and the Politics of Exclusion since Ibn Khaldun:

Epilogue: Historicizing the Enemy, Globalizing Islam, Giving Violence a New Name

“It is merely in the night of our ignorance that all alien shapes take on the same hue.”

(Perry Anderson, Lineages of the Absolutist State)

Historicizing the Enemy

I began this book with the attempt to restore Islam to a code of knowledge by considering a protracted modern history of encounters with the West and the corresponding personal sensibilities as well public discourses that emerged from those encounters, especially in the field of intellectual history. The conflict with Islam today, for which both Western Europe and America are fully militarized, will not be resolved simply by more “accurate” and intensive historical research, just as an understanding of the sensibility of the Arab-Islamic world requires more than political pacification and campaign promises, and definitely more than the passionate attempts at guarding the values of the so-called global world against the “fanaticism” of Islam and its adherents.

My concluding thoughts depend not so much on exposing post-9/11 Islamophobia as on emphasizing that this Islamophobia is the lingering effect of a crooked history of oppression that not only legitimized colonial and imperial domination in the last century, but also managed to reproduce itself in the postcolonial and sustain its underlying xenophobic codes up to the present day. Against the continuity thesis of this pernicious dogma, one cannot but return to history. I am not arguing that history repeats itself, for this is another ignis fatuus that many cyclical historians like to chase. To me, history matters not only because it positions the present geopolitical understanding of Islam in relation to important contexts of colonialism, decolonization, and globalization, but also because it has become a discourse of conquest.

As a critique of colonialism and violence finally took place in the heart of Europe towards the end of WWI, leading to the Versailles Treaty of 1917, problematic categories of humanism, freedom, democracy, civilization, and equality came into question. The Treaty itself was convened in the spirit of such ideals. Not only did Europe take its own values for granted in the Versailles Treaty, seeking to apply them to its colonized subjects, but it ironically failed to uphold these same ideals. The Versailles Treaty was therefore a major disappointment to colonized subjects and to anti-colonial movements in general within Europe and abroad.[1] Not one single occupied Arab country would gain its independence from European colonialism before 1950: Libya (Italy) in 1951, Sudan (Britain), Tunisia (France), and Morocco (France) in 1956, Iraq (Britain) in 1958, Kuwait (Britain) in 1961, Algeria (France) in 1962, South Yemen (Britain) in 1967.

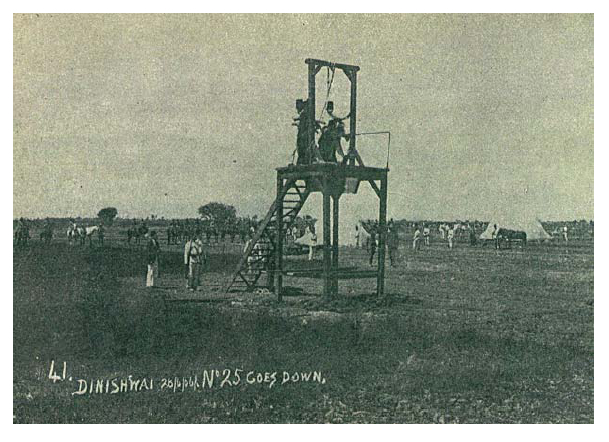

As we have seen in the example of the Denshawai affair, colonial violence remained present in public, not only in Egypt but throughout the Arab world, until the second half of the twentieth century. Long after gibbeting and public hanging in chains were abolished in England (in 1832 and 1834 respectively), both were still practiced in the colonies. It is difficult to ignore the remarkable similarity between France’s torture of Algerian natives and labeling of them as terrorists and America’s torture of Iraqis in Abu Ghraib.[2] This is not just a manifestation of Western power but a continuation of the logic of industrial modernity responsible for producing the technology and the machinery that equipped colonialism. Without the dichotomous logic of this modernity, which split the world into powerful and powerless states, and without its insidious metamorphosis into one superpower, there would have been no colonialism.

[A photograph of the British execution of Egyptian peasant Zahraan in Denshawai, in what is infamously

known as the Denshawai Affair of 1906. Image from unknown archive.]

I am not arguing that European and American intervention in the Middle East justifies terrorism, or that Western bias against the Arab world is responsible for the emergence of Islamic fundamentalism or the horrifying events of 9/11. Nothing justifies crude, unprovoked violence. We should have no tolerance for disrespect of human life, and there is no excuse for the cold-blooded killing of innocent civilians. But we must not forget that the West had an important role to play in nourishing the soils where the belligerent ideologies of terrorists germinated and thrived.[3]

With the fall of communism, America has replaced the threatening Russian Other with the ominous Islamic Other in a remarkably short span of time.[4] Confronting this Islamic Other in all its difference and menace, and all its internal and external danger, has certainly been one of the main challenges for United States security even predating 9/11, not only because of the terrorist activities of groups like al-Qaeda, but also because the United States has made enemies by imposing its political will on many national and international decisions made in the last fifty years, from Sukarno in Indonesia to Nasser in Egypt, from oil economy to outer space, and from the UN to NATO.

This interventionist policy has prompted some writers to address the coming into being of the United States as the Empire of a new Eurocentric system of social and economic control.[5] But just as postmodernity today is not restricted to Euro-America or a defined geographical space, Eurocentrism too must be understood in transnational and global terms. As Arif Dirlik puts it, “a radical critique of Eurocentrism must rest on a radical critique of the whole project of modernity understood in terms of the life-world that is cultural and material at once.”[6] For this reason, the current operating assumptions of the world compel us to persist in critiquing Eurocentrism in its post-national, post-theological, and postmodern manifestations. A serious critique of Eurocentrism must confront contemporary world issues and examine notions like terrorism, globalization and cosmopolitanism in order to assess their relationship to power in its vicious circularity, both as a product of culture and as culture producing. The transformations of the global economy, the economic, political, and military dependency of the new nation-states of the Middle East on Europe and America, and the hybridity of post-national and post-theological cultures are all telling examples of this power’s capacity to manifest itself in various forms. But first, we need to ask direct questions: how do we reach operative definitions of terms like “globalization” or “cosmopolitanism,” and where do we situate Islam in relationship to them? Even more explicitly, what are the characteristic “international” features of globalization and what belief system(s), if any, does it include or exclude; what sort of culture(s) does globalization incorporate, and what political postulates does it embrace?

[1] See Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 240-241.

[2] Ironically, U.S. military officials used the newly digitalized version of Gillo Pontecorvo’s Fanon-inspired film La Battaglia di Algeri (The Battle of Algiers) as an instructional visual for their planned strategic occupation of Iraq. Pontecorvo’s film includes numerous torture scenes and opens with a stark shot of an old Algerian man physically exposed and brutally tortured by the French Occupation Army. The film was considered a manual for revolutionary success against superior force, for in the end Algiers would prove to be France`s most humiliating loss in the same manner that Vietnam was destined to become America`s most embarrassing defeat. See Maria Esposito’s interview with Gillo Pontercorvo, “Stay Close to Reality,” World Socialist Website (9 June 2004).

[3] See Aijaz Ahmad, “Islam, Islamism, and the West,” Social Register (London: Merlin, 2008), 25.

[4] See Edward Said, Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World (New York: Vintage, 1997).

[5] See Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

[6] Arif Dirlik, “Is There History after Eurocentrism?: Globalism, Postcolonialism, and the Disavowal of History,” Cultural Critique, No. 42 (Spring, 1999), 1-34.

[Excerpted from Mohammad R. Salama, Islam, Orientalism and Intellectual History: Modernity and the Politics of Exclusion since Ibn Khaldun. © 2011 by I. B. Tauris. Reprinted with the permission of the author. For more information, or to purchase the book, click here.]

![[Cover of Mohammad R. Salama`s book \"Islam, Orientalism, and Intellectual History\"]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/Screenshot2011-08-25at1.07.48AM.png)